Codex, 2017

This past Sunday I went to Codex, a biannual book fair held at Craneway Pavilion in Richmond. When I say ‘book fair,’ though, that really doesn’t do this event justice: it’s a four-day extravaganza, offering an astonishing range of exquisitely-printed small press books. The mission of Codex is to ensure the future of the art and the craft of printing, supporting the community of makers in no small part by connecting them with collectors, of both the private and institutional variety. Libraries with rare book collections come to Codex to shop.

This year’s fair was number six. When I attended the prior one, held in 2015, I was immediately smitten by the vast building where it takes place (a Ford assembly plant in a previous lifetime) and the panoramic views of San Francisco it offers from its waterfront location. Once inside, I was bowled over by the astonishing world of bibliophilia that was on display.

This time, as on my previous visit, the enormous room was filled with rows and rows of tables, each one covered with beautifully handmade, hand bound books in small editions, unique book art and art made out of books-- and even bookmaking materials. There were over 200 exhibitors from all around the world, including 11 artists from China, the focus of this year’s symposium (a series of presentations that takes place over the first couple of mornings of each fair, before the afternoon sales event begins).

Not surprisingly, northern California was heavily represented. The Bay Area is a hotbed of art-of-the-book activity. There were also at least a half a dozen exhibitors from Iowa, possibly due to the University of Iowa’s Center for the Book, and many from in and around New York and other locations across the US.

As I walked up and down each aisle, I saw lovely work from Mexico and Canada, France and Germany.

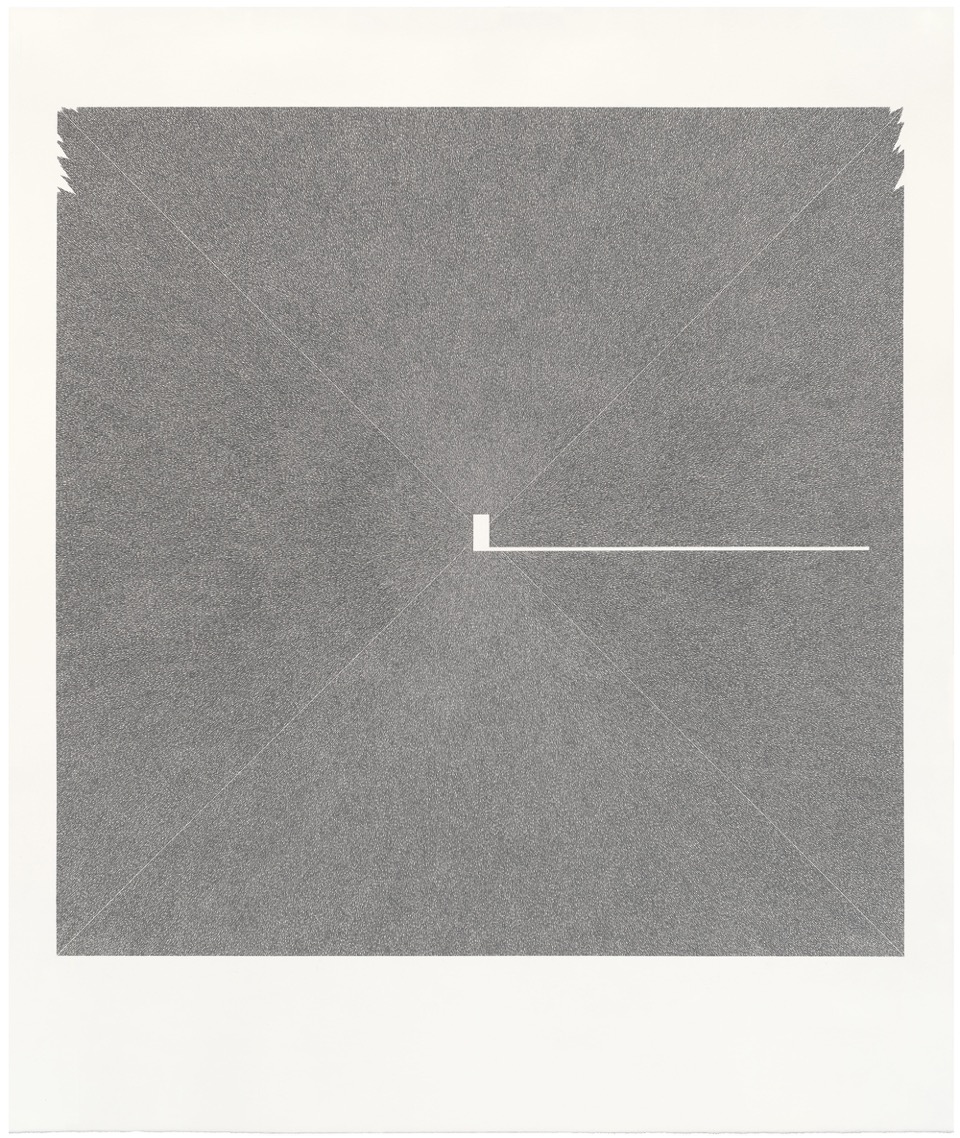

This handsome example of typography from the Irish REDFOXPRESS caught my eye. There were book makers and sellers from Israel, Australia, Russia, Switzerland, Japan.

Standing behind a table filled with delicate, wonderful book objects created with a combination of laser cutting and traditional binding techniques, Islam Aly represented both Cedar Falls, Iowa, where he lives now, and his native Egypt. Schools with book programs, including Oakland’s own Mills College, had tables as well.

At the last Codex, I was entranced with artist Nancy Loeber’s portraits: woodblock prints in delicate colors. Back at the fair again, she was showing a portfolio of imaginary brothers and sisters, and a book titled Lord Byron’s Foot(!!).

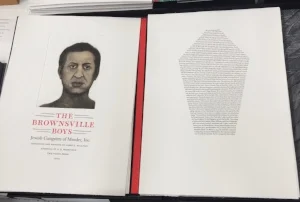

A handsome example of text as art could be seen in the coffin-shaped page of words facing the title page of The Brownsville Boys: Jewish Gangster of Murder, Inc., by Two Ponds Press.

While my predominant memory of the fair is of exquisite and even poetic books in attractive, tasteful bindings, there were also moments of comic relief. I adored Sarah Nicholl’s Field Guide to Extinct Birds.

Engine and Well of Iowa City offer a wordless version of the familiar story of Jack and the beanstalk, told in a succession of bold woodcuts printed on a several-foot-long scroll, rolled up and sealed into a can labeled BEANS.

And Maureen Cummins’ word plays, both dark and funny, demand close attention. On the cover of a metal book (bottom right of photo) about the ‘father of the lobotomy,’ the word therapist is broken into its component parts, the rapist, a secret meaning reflected in the revelations offered by the text within. Other titles included similarly plangent plays on words.

Like any art fair, if you really want to see everything, two visits (or incredible endurance) are required to really absorb all of the objects and ideas on display. I had many conversations that, though brief, were deeply enjoyable, because everyone was so friendly. But I wished I had more time—something I rarely want, at such events. Though crowded, it never felt anything less than civil and calm.

And now to some observations, that are simply that: not judgments, but a record of what I saw at both Codex fairs I have visited. Attendees (and for the most part exhibitors) are a very homogeneous group. They are almost entirely white, between the ages of forty-plus and seventy-five; unlike the visitors at many art fairs, rather than suits or black clothes, they wear flowing scarves and sweaters in neutrals or the same tasteful hues as the book bindings on the tables. I saw a handful of children (as in, less than five). The ticket price isn’t prohibitive-- $10 is less than a movie, these days, and half of what it costs to get into SFMOMA— but it’s still significant. (Thousands visit, according to the Codex website, but, as with other art fairs, those who do represent a distinct demographic.

One can only hope that future Codex attendees will include additional younger enthusiasts. Still, I remember having some of the same anxious hopes at a symposium put on by the American Craft Council a few years ago, when I looked out over the heads of the crowd and the majority of them were gray. That, of course, was before the Internet really got going as an engine of commerce. Nowadays the crafts world seems to be surviving nicely, including all kinds of letterpress-printed whatnots (cards, coasters, limited edition art) that are selling like hot cakes all over Etsy and through Instagram posts. So maybe there is no need for Codex to try to appeal to anyone other than the group that supports it—a community that is internationally diverse, if somewhat skewed towards retirement age.

Someone will always love books, and words, and want to run her fingers over paper in which type or image have left a crisp impression.